The Future of European Industry Needs a Financing Evolution The Role of Private Debt in Financing Reindustrialisation

Sunny CHHABRA, Senior Analyst chez Ironshield Capital Management LLP.

Executive Summary

In a world reshaped by inflation, geopolitical fragmentation and regulatory tightening, the traditional methods of corporate financing in Europe—particularly France—are being stretched to their limits. With public sector borrowing crowding out private capital and Basel IV eroding banks’ lending capacity, we believe European companies are at a pivotal juncture.

Private debt, once seen as peripheral, is emerging as a central pillar of industrial financing. In this paper, we explore how the rise of direct lending and disintermediated capital is not just a contingency plan—but a necessary evolution. We draw comparisons with the UK and US, examine why the current moment is different, and argue that private credit is not just viable—it’s critical.

At Ironshield Capital, we operate at the heart of this evolving landscape—focused exclusively on sub-investment grade credit in Europe’s secondary markets. This vantage point offers us a unique perspective on the pressures building beneath the surface of traditional financing channels.

The repricing of risk, the wall of maturities, and the retreat of bank capital are not abstract trends—they are visible daily in secondary trading flows. As more corporates confront refinancing hurdles and legacy debt structures, we believe the secondary market will increasingly serve as a barometer of stress and a source of opportunity. Companies can take advantage of better opportunities by turning to private debt financing in the future thanks to the revitalization and growth of the secondary market for private debt. We have been active in the secondary market for the past 18 years, and our experience puts us in a strong position to interpret these signals and translate them into profitable investments.

1. The European Dilemma: Strong Banks, Weak Flexibility

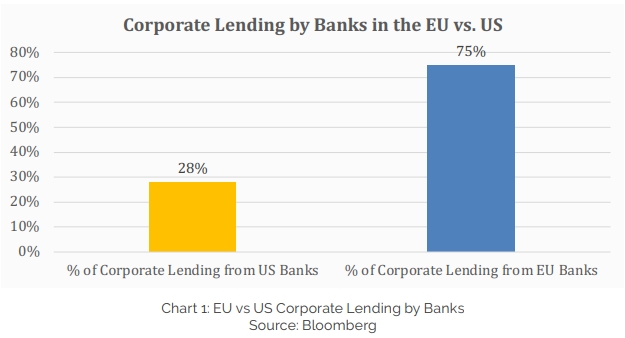

French companies remain heavily dependent on bank financing—close to 80% of corporate credit originates from traditional banks. But we are now seeing the constraints of that model. Basel IV, set to take full effect by 2028, imposes tougher capital rules, limiting banks’ appetite for SME and sub-investment grade lending. ESG mandates, DORA, and risk-weight recalibrations will disproportionately affect smaller borrowers.

To compound matters, France’s public debt is at record highs—spending 55% of GDP with 40% of its fiscal deficit stemming from social programs and pensions. The state is crowding out the very capital that mid-sized industrial businesses need to expand, innovate, and hire.

This is not a theoretical issue. With €500 billion in new German borrowing and France’s defence budget rising by €118 billion, institutional capital will increasingly be diverted to sovereign debt.

Private credit can act as a pressure valve in this system. When banks retrench, funds can step in with creative capital solutions—ranging from growth capital to acquisition finance to rescue loans. But for this to scale, education and policy support must meet capital.

2. Learning From the UK and US: First-Mover Advantage

In the UK, while the majority of credit still flows through banks, there is a much healthier balance. Bank lending constitutes approximately half of the total outstanding debt for UK companies. Larger firms often access alternative financing sources, such as capital markets, indicating a substantial role for non-bank entities in corporate finance. Institutional capital—particularly from pension funds, insurers, and alternative lenders—has long played a key role. The US goes even further, with fewer than 50% of corporates reliant on bank lending.

Furthermore, the non-bank specialist lending sector (NBSLS) is notably active in areas like small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) finance, mortgage lending, and consumer credit. It’s estimated that about 30% of all SME finance in the UK comes from non-bank sources.

Additionally, the UK commercial real estate (CRE) lending market has evolved significantly. In 2009, it was entirely dominated by banks, but by 2023, banks accounted for only 60% of the market, with the remaining 40% served by insurers and other non-bank lenders.

Why does this matter? Because countries with deep private markets recover faster, finance innovation more efficiently, and reduce systemic risk by spreading credit exposure across diverse investors.

This is not just theory. It is observable in every cycle. During COVID-19, the US corporate bond and private credit markets absorbed huge volumes of refinancing activity. In Europe, much of the burden fell on government-guaranteed loan schemes.

As governments now attempt to roll back those guarantees, a vacuum is emerging—one that private lenders are well-positioned to fill.

We’ve seen it before: companies that failed to adapt—Blockbuster, Kodak— became cautionary tales. European corporates face a similar tipping point. Will they embrace alternative capital, or cling to legacy relationships at their peril ?

3. Structural Opportunity: A Wall of Refinancing Meets a Shallow Pool

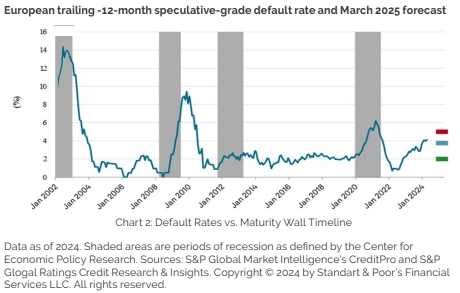

From 2026 to 2028, nearly 50% of European high yield bonds mature. These bonds were issued during the era of zero rates. That era is over. Companies that fail to refinance early—before distress sets in— risk punitive terms or outright default.

As of 2024, European private equity sponsors held approximately €453.5 billion in cumulative dry powder, indicating a significant capacity for deal making without the immediate need for additional fundraising. Furthermore, the top 20 private credit managers globally accounted for $138.14 billion in uncommitted capital, representing 36% of the total $385.28 billion in global private credit dry powder.

This substantial accumulation of capital positions these managers to offer comprehensive financing solutions, including convertible debt, holding company financing, and debt-for-equity restructurings, effectively addressing the refinancing demands anticipated in the European market.

The debt maturity wall is also a pricing signal. It tells us that companies who act first—those who refinance in 2025— will enjoy better pricing, more flexible covenants, and deeper liquidity. The challenge, however, is that many companies are sitting on debt raised during the zero-rate era—some at coupons as low as 2% to 3%. Refinancing that today could mean accepting rates closer to 8% to 12%, depending on credit quality, leverage, and liquidity position. Understandably, CFOs are hesitant to lock in materially higher costs of capital unless absolutely necessary.

But waiting comes with real risk. As more companies cluster around the same refinancing window in 2026–2028, competition for capital will intensify. Banks, already constrained by Basel IV and sovereign exposure, will prioritise their best relationships. Private credit will likely be selective and demand stronger covenants or equity-like returns. Liquidity will narrow—and pricing will worsen.

In that environment, the companies that delayed may find themselves boxed out entirely, especially if macro conditions deteriorate or their fundamentals weaken. Worse, lenders will view them as reactive rather than proactive—leading to more defensive, covenant-heavy terms or requiring equity injections to close deals. Acting early, even at a higher rate, offers optionality. Waiting might mean accepting terms under duress.

4. What’s Holding France Back? Culture, Control, and Coordination

Many French businesses fear that engaging with non-bank capital providers could sour long-held banking relationships and loose future potential funding with higher barriers to entry. In a concentrated system, the risk of being “cut off” is real. But inaction may be even riskier.

Perhaps there is also an education gap. Do SMEs and mid-sized firms know how to access private credit markets or lack the in-house treasury or legal expertise to negotiate complex debt instruments. Some forward-looking corporates are already moving. The UK and Germany— where the ‘Schuldschein’ and bilateral lending culture is stronger—are years ahead. France must now catch up or be left behind. Other European countries with similarly bank-centric systems— such as Spain, Austria, and even parts of Scandinavia—risk falling into the same trap. These markets tend to be dominated by domestic banks, with limited penetration by alternative lenders and less-developed private capital ecosystems. Without a deliberate push to diversify funding sources, these economies could struggle to support their industrial sectors through the next cycle of capital investment and refinancing. The risk is a widening competitiveness gap within the eurozone.

Spain:

• Historically, Spain has relied heavily on bank financing. However, the consolidation of the banking system from 55 banks in 2009 to just 13 by H1 2020 has reduced the number of bank players, creating opportunities for direct lenders to expand their market share from the current 20%.

• The Alternative Fixed Income Market (MARF), established in 2013, has gained importance as a means for Spanish companies to diversify their financing sources, offering more flexible structures and time frames than traditional bank loans.

Austria:

• In 2021, domestic banks were the primary source of debt financing for the Austrian corporate sector, accounting for 54% of net debt transactions, primarily through bank loans totaling EUR 16.0 billion. This indicates a significant reliance on traditional bank lending.

• The external financing of Austrian non financial enterprises is mainly carried out through equity and loans, with alternative financing forms playing a lesser role.

Scandinavia:

• In the Nordic region, direct lending comprises less than 5% of middle-market financing transactions, compared to more than half in the UK. This suggests a lower penetration of alternative lenders and a continued dominance of traditional banks in corporate financing.

• Alternative lenders have been stepping in to fill the space left by banks across Europe since the 2008 financial crisis and are beginning to catch up in Scandinavia as well.

And there’s a broader psychological hurdle. Risk committees within banks are conditioned to lend based on historical models, even as forward-looking volatility increases. Private credit can take a view on forward-looking cash flows, not just backward-looking financials.

This makes it an ideal tool for reindustrialisation, where capital is needed to fund transformation—not just maintenance.

5. The Policy Angle: From Tibi to Tipping Point

France’s Tibi initiative channeled €6 billion into venture and tech. Why not do the same for industrial credit? A public private initiative to co-invest in French SMEs through private debt strategies could stimulate growth without adding to the state’s balance sheet.

Some ideas:

• Launch a «Tibi Credit» programme: allocate €5bn to mid-cap and industrial private debt

• Allow insurers to count private credit towards Solvency II capital buffers at lower charges

• Build a national SME ratings agency to improve visibility for private lenders

• Create ESG-linked performance bonds supported by government backstops

The question isn’t whether capital exists. It does. The challenge is matching it with opportunity—through better visibility, less friction, and confidence that companies can engage without alienating their existing banks.

6. Why Now? And What Happens If We Wait ?

Timing matters. This is a window where capital is still available, maturity walls are visible, and macro uncertainty hasn’t fully crystallised. Acting now means optionality. Waiting means reacting.

Governments are under fiscal pressure. Banks are under regulatory pressure.

And global investors are increasingly demanding real yields with downside protection. That’s a perfect setup for private debt.

We believe:

• The next 12–18 months will set the trajectory for European SME and midcap financing

• First movers will access better terms, better lenders, and avoid forced restructurings

• Delay may mean loss of control and value destruction

Conclusion: A Financing Crossroads for European Industry

Europe’s financial architecture is at a crossroads. Reindustrialisation requires massive capital deployment. Traditional bank channels are no longer sufficient. Sovereign debt will continue to crowd out risk capital. Basel IV will tighten further. And the maturity wall is approaching.

Private debt is not an exotic alternative. It is the only credible response to these structural shifts.

The question is no longer if European companies should diversify their funding base. It’s when—and how quickly. Early movers will secure better pricing, preserve strategic flexibility, and avoid restructuring. Late adopters may find that when they need capital most, it’s no longer there.

In our view, this is Europe’s Blockbuster moment. The future belongs to those who modernise—before they must.

Sunny CHHABRA

Senior Analyst chez Ironshield Capital Management LLP